The Pedagogy of Liberation: What the Classroom Owes the Community

"Education is about legacy. Dr. Aisha Rahman reimagines the classroom as a space for healing, history, and freedom."

By Dr. Aisha Rahman | Black Writer's Club

November 4th, 2025

Before there were classrooms, there were porches, pews, and kitchen tables, the original universities of our people. Lessons weren’t written on whiteboards; they were sung in hymns, whispered in kitchens, and carried through the calloused hands of elders who understood that knowledge is not a product of institutions, but a birthright of survival.

When I step into a classroom today, I don’t see rows of desks, I see a lineage. I see the ancestors who dreamed of literacy as rebellion, of books as open doors. And yet, I also see the ways our systems have forgotten this truth. The modern classroom too often teaches content without context, vocabulary without voice. Students memorize what has already been approved instead of exploring what has been omitted. That is not education, that is containment.

True education begins when we allow history to speak in its full complexity. When we refuse to reduce the Black experience to trauma or tokenism, and instead teach it as a living, breathing ecosystem of art, intellect, and innovation. To do that, we must first expand our definition of curriculum. A curriculum should not be a cage, it should be a mirror.

When I teach, I weave oral history alongside literary theory. I ask my students to bring the voices of their grandmothers into the room, the proverbs, the sayings, the coded wisdom that kept families alive long before standardized tests existed. Because the classroom owes its community a reckoning: it must acknowledge the genius that thrived without credentials.

"The classroom must become a living archive, not a mausoleum for dead facts..."

And the work is already happening. In Baltimore, educators at the Liberation Academy are using hip-hop and local oral histories to teach civics and critical thinking. In Chicago, teachers are redesigning social studies around neighborhood storytelling. Across the South, small after-school collectives are gathering children around kitchen tables again, reminding us that the most radical education sometimes looks like love, structure, and memory stitched together. These are not experiments, they are the blueprint.

The pedagogy of liberation is not about replacing one canon with another. It’s about dismantling the idea that knowledge has an owner at all. Every community, every lineage, carries its own library. The educator’s job is not to curate what’s “valid,” but to make space for what has been silenced, and to remind students that learning is not a performance for approval, but a practice of becoming.

When my grandfather told stories from his griot traditions, he never called them “lessons.” But each one was a map, a way of remembering who we were so we could imagine who we might still become. That, to me, is the task of education today: not to manufacture understanding, but to recover it.

Our classrooms must become sanctuaries of possibility again. Places where Black students see themselves not as footnotes to a nation’s history, but as architects of its future. If literacy is the key, then legacy is the door, and liberation is what waits on the other side.

To every educator, writer, and student reading this: may we teach as if our classrooms are extensions of the community that built us, because they are.

True liberation in education begins when we remember that teaching is not about control, it's about care. The classroom, at its best, is a sacred space for transformation. And every time a student sees themselves in the story, the revolution continues.

Inspired by this essay? Join the conversation.

Follow Black Writer’s Club for stories, interviews, and essays redefining the culture through language.

About the Author:

Dr. Aisha Rahman is an essayist and educator whose work bridges scholarship, storytelling, and social justice. She explores how language, history, and heritage intersect in modern education. Through her essays and workshops, she continues the tradition of Black women educators who teach not just for literacy, but for liberation.

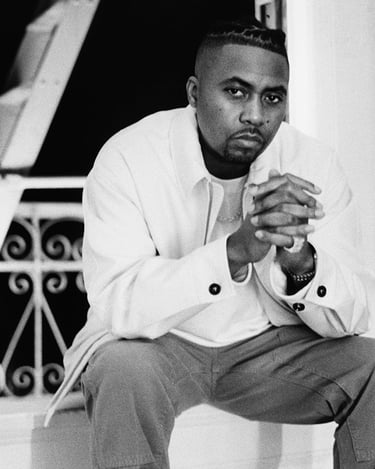

STILLMATIC: The Poet in the Cypher

By Kwame Osei | Black Writers Club

November 4th 2025

“Some stories don’t get told, they get rhymed into existence.”

Queensbridge was a prophecy, not an address.

Every brick carried a verse. Every hallway hummed like a horn section. When Nas stepped to the mic in ‘94, he wasn’t introducing himself; he was documenting us. Illmatic wasn’t an album, it was an act of translation. He took the language of the block and turned it into scripture.

I hear Nas the way my elders heard Coltrane, language stretched until it became spiritual. His flow was architecture: rhythm as blueprint, survival as design. He taught us that lyricism could be literature, that the corner could contain the cosmos.

I. The Poet

Nas’s pen was precision. He didn’t just describe struggle, he distilled it. Each line from It Ain’t Hard to Tell felt like Baldwin in Timberlands, Baraka with a boombox. His words carried the weight of witness.

And in a country that often silences the witness, he forced America to listen.

But beneath the critique lived craft. Nas mastered the balance between introspection and performance, every verse a mirror and a mask. When he said, “I never sleep, ‘cause sleep is the cousin of death,” he turned insomnia into insight, paranoia into poetics.

II. The Prophet

Then came Stillmatic. The return of the griot.

By then, hip-hop was shifting, the money louder, the message quieter. Yet Nas re-emerged with fire in his lungs and clarity in his eyes. He wasn’t chasing relevance. He was chasing revelation.

Albums like God’s Son and Untitled revealed a man unafraid to question his own crown. He rapped about evolution, about trying to be holy in a haunted world. He wasn’t preaching, he was processing. That’s the difference between a prophet and a performer: one entertains; the other endures.

III. The Paradox

Here’s the truth most won’t say: Nas is both blueprint and contradiction. He is what happens when genius grows older under capitalism. The poet becomes a brand, the hunger becomes heritage. Yet even now, in King’s Disease and Magic, he’s finding new language for legacy, showing us how to age without fading, how to sharpen without bitterness.

IV. The Legacy

Nas didn’t just rhyme; he remembered.

He preserved our pain in rhythm and built bridges from the Bronx to the diaspora. He reminded us that hip-hop was never just about beats and bars, it was about building meaning out of madness.

“The poet’s job is to translate chaos into chorus. Nas did that. Still does.”

And that’s why we still call him Stillmatic. Because he’s still making sense of the noise. Still mapping our way home.

Inspired by this essay? Join the conversation.

Follow Black Writer’s Club for stories, interviews, and essays redefining the culture through language.

About the Author:

Kwame Osei is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic whose work explores Black identity, art, and memory across the diaspora. His writing merges lyricism and social critique, turning observation into resistance and rhythm into revelation.

In a world that worships realism, imagination becomes rebellion. Lena Jenkins, novelist and screenwriter, explores why dreaming beyond constraint is not luxury but survival, and why every Black creator’s act of imagination is a political act.

In Defense of Imagination

By Lena Jenkins | Black Writer’s Club

“Imagination has always been our inheritance. From the hush harbors to the writer’s room, we’ve imagined our way out of cages.”

They love to tell us to be realistic. As if realism has ever saved anyone. As if being realistic could ever dismantle a system built on fantasy, the fantasy of whiteness, the fantasy of control, the fantasy that our brilliance must be contained.

When I was a girl in Atlanta, my grandmother would whisper stories into her transistor radio late at night. Her voice would slip through the static like a secret frequency, carrying whole worlds across invisible airwaves. That was how I learned that storytelling is not decoration; it is defense. Every tale was a code. Every fable, a blueprint. We were not merely surviving. We were world-building.

For Black writers, imagination is not an escape. It is strategy. It is how we reroute trauma into technology, grief into language, memory into blueprint. To imagine a different future when the present feels immovable, that is an act of revolution.

That is why I refuse to apologize for my work living between genres. One scene may belong to 1935 Harlem, the next to a post-apocalyptic Lagos, because time has never been linear for us. We have always bent it, remixed it, and survived inside its folds.

When I write, I am not simply dreaming. I am coding. Each story becomes a simulation of freedom.

“Realism was their weapon. Imagination was ours.”

“Each story becomes a simulation of freedom.”

The literary world loves its boxes, literary, sci-fi, urban, romance, as if our lives could fit neatly into subcategories. But what do you call a story that begins in a sharecropper’s field and ends in a spaceship? What name fits a woman who is both ancestor and algorithm?

This is why I write the way I do: defying the borders that publishing built to contain us. Genre is a gate, and I am here to dismantle it.

Toni Morrison once said, “To limit the imagination of a people is to limit their freedom.” I believe her. But I would add: to police our imagination is to reveal fear, fear of what we might create, and fear of what our creation might undo. And make no mistake. They fear it.

When I speak of Afrofuturism, I am not talking about silver suits or laser beams. I am talking about possibility, the right to envision ourselves in tomorrow’s archive. I see a generation of Black women turning wounds into worlds: poets becoming coders, novelists composing digital sermons, filmmakers constructing alternate histories where we win. Every act of creation becomes an act of refusal.

“The future isn’t something we wait for. It’s something we write into existence.”

Whenever I sit down to write, I think of that radio humming in my grandmother’s kitchen, the static, the warmth, the danger. She didn’t know it then, but she was already broadcasting to the future.

Now it is our turn to transmit. To speak in frequencies that power cannot decode. To create stories so alive they refuse to stay on the page. Imagination has always been our inheritance. It is time we defend it as sacred, because it is.

Inspired by this essay? Join the conversation.

Follow Black Writer’s Club for stories, interviews, and essays redefining the culture through language.

About the Author:

Lena Jenkins is a novelist and screenwriter celebrated for reimagining the presence of Black women in speculative fiction and contemporary drama. Raised in Atlanta within a family of storytellers and radio pioneers, she crafts narratives where legacy, innovation, and Afrofuturism entwine. Her stories challenge norms and envision new futures for Black literature and film.